RECENT CASE STUDIES

The Rise of Public Sector Banks in India’s Economic Revival Post-Pandemic

Last updated: Nov, 2025

Public Sector Banks (PSBs) represent one of India’s most remarkable turnaround stories in its recent economic history. These financial institutions, defined as commercial banks in which the Government of India (GOI) holds a majority stake of 51% or more, have undergone a dramatic transformation from being burdened by mounting Non-Performing Assets (NPAs) to becoming the driving force behind India’s banking sector’s profitability. PSBs have evolved from being institutions weighed down by bad loans to becoming a resurgent force that underpins the country’s post-pandemic economic revival.

The importance of PSBs goes well beyond their financial measure. These banks are the major financial lifeline to millions of Indians who are still unable to access the formal banking system, which is dominated by their private sector counterparts. Government ownership carries an implicit sovereign guarantee; depositors have thus historically felt more secure, not just with commercial banks, but with PSBs, which makes PSBs the bank of choice among susceptible groups such as the elderly, rural folks and first-time banking customers.

The transition of PSBs to recovery provides lessons on organisational possibilities that can be unlocked through strategic policy, alongside operational reforms and technological improvement, in even the most imperilled financial institutions. This change is more interesting because numerous state-owned organizations, globally, are faced with inefficiency and unprofitability. India’s PSB resurrection shows that the right combination of recognition, resolution, recapitalisation and reforms – the 4R approach – can turn around even severely damaged institutions to a path of health and profitability.

Understanding public sector banks: Definition and distinction

Although PSBs are commercial institutions regulated by the Banking Regulation Act and governed by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), they are government-majority-owned institutions that open opportunities as well as challenges that define their operational dynamics. This form of ownership allows PSBs to address wider growth and social needs that would not be commercially feasible for profit-making, private-sector banks.

The difference between a public and a private-sector bank is especially stark in the area of operational philosophy and market positioning. Even when these activities may not yield returns in the short-term, PSBs have a long history of attending to areas of financial inclusion, priority-sector lending and government-initiated policy endeavours. Meanwhile, private banks are more agile in city markets and focused on clients that are beneficial to profit margins – are likely to focus on smaller/niche markets or customers that are part of higher income brackets. Such inherent variation in strategy has established a complementary ecosystem of banking in which PSBs guarantee widespread reach of financial services while privately held banks spur innovation and efficiency benchmarks.

The current landscape features 12 major PSBs following the consolidation drive of 2017 to 2020: State Bank of India (SBI), Bank of Baroda, Punjab National Bank, Canara Bank, Union Bank of India, Indian Bank, Bank of India, Bank of Maharashtra, Central Bank of India, Indian Overseas Bank, UCO Bank, and Punjab & Sind Bank. These institutions collectively command a significant share of India’s banking business, with their extensive branch networks serving as the backbone of the country’s financial infrastructure.

Historical evolution: From imperial legacy to modern banking

The roots of India’s public sector banking system can be traced to the colonial era when the Imperial Bank of India was established in 1921 through the amalgamation of the three Presidency Banks – Bank of Bengal, Bank of Bombay, and Bank of Madras. This consolidation represented the first major attempt at creating a unified banking entity that could serve the vast Indian subcontinent. The transformation of the Imperial Bank into the State Bank of India in 1955 marked the beginning of India’s systematic approach to state-controlled banking, setting the foundation for what would eventually become the world’s largest network of government-owned banks.

Waves of nationalisation in 1969 and 1980 significantly changed the context of the Indian banking sector. The initial wave of 1969 nationalised 14 of the largest major private banks, consisting of already existing banks such as Central Bank of India, Punjab National Bank and Bank of Baroda. In 1980, another six banks were nationalised, including Andhra Bank, Corporation Bank and Vijaya Bank. The rationale was that nationalised industries could allocate credit to priority sectors and disadvantaged regions with the socialist-oriented economic policies of the time, which had a wider impact on such nationalisation efforts.

Nationalisation was more than simply a government takeover of the banks; it was an explicit policy decision to make banking one of the tools of economic transformation and social reform. The newly nationalised banks were to provide financial services to the rural sector, small industries and also accommodate the various government scheme rollouts. Although such a role in development improved social good, it would also in the future trigger difficulty as commercial potency at times interfered with social goals.

Pre-pandemic crisis: The NPA challenge

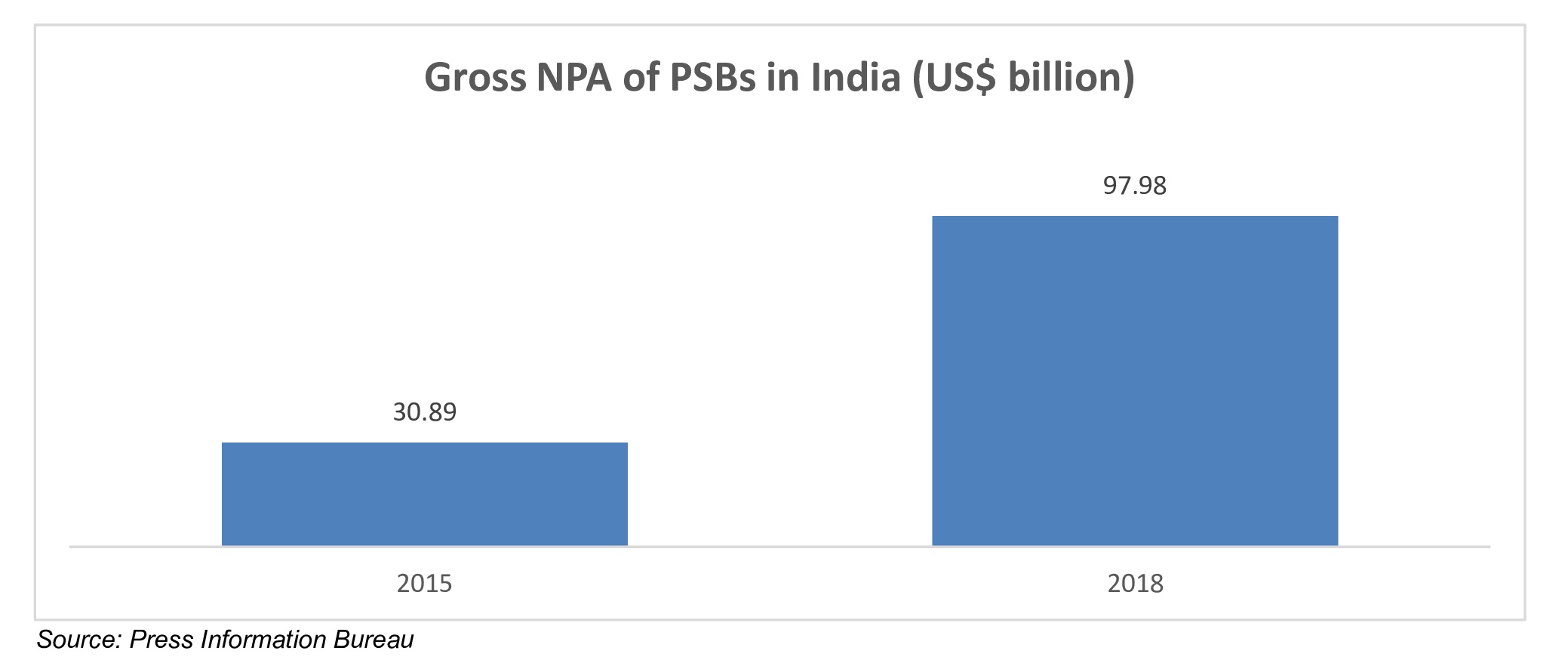

Prior to the onset of the pandemic, the asset quality crisis in India’s PSBs was so severe that it challenged the very existence of the Indian public banking system. The gross NPA of PSBs had alarmingly increased by over three times to Rs. 8,45,475 crore (US$ 97.98 billion) as of March 31, 2018, as against the Rs. 2,67,065 crore (US$ 30.89 billion) as of March 31, 2015, a rise of more than three times in three years alone. This downturn in asset quality was not just a statistical problem, but a structural problem that has been accumulating over the last decade.

The origin of this crisis dates back to a time of excessive lending in India during the high economic growth period over 2003-2008. In the process, PSBs built their corporate lending books extensively, especially in small-scale infrastructure projects, power, steel and telecommunications. A good proportion of these loans was approved based on rosy projected assumptions and on optimistic economic times that reigned throughout the boom years. But as world commodity prices crashed and domestically driven economic growth slowed after 2011, many such projects turned out to be unviable, resulting in rampant defaults.

The regulatory environment of the time inadvertently contributed to the problem through various forbearance measures that allowed banks to defer the recognition of stressed assets. Schemes such as Corporate Debt Restructuring (CDR) and various restructuring packages permitted banks to avoid classifying problematic loans as NPAs, creating an illusion of asset quality that masked the underlying stress[5]. This regulatory forbearance, while intended to provide breathing space for recovery, ultimately delayed the necessary corrective actions and allowed problems to escalate.

The situation was further worsened by the failure of governance in several PSBs whereby credit decisions were occasionally influenced by factors other than sheer commercial viability. External economic factors (mainly the pressure on financial reserves), regulatory forbearance and internal problems of governance all combined to cause the perfect storm and led the PSB category to the edge of a systemic crisis by the mid-2010s.

The 4Rs strategy: A comprehensive reform framework

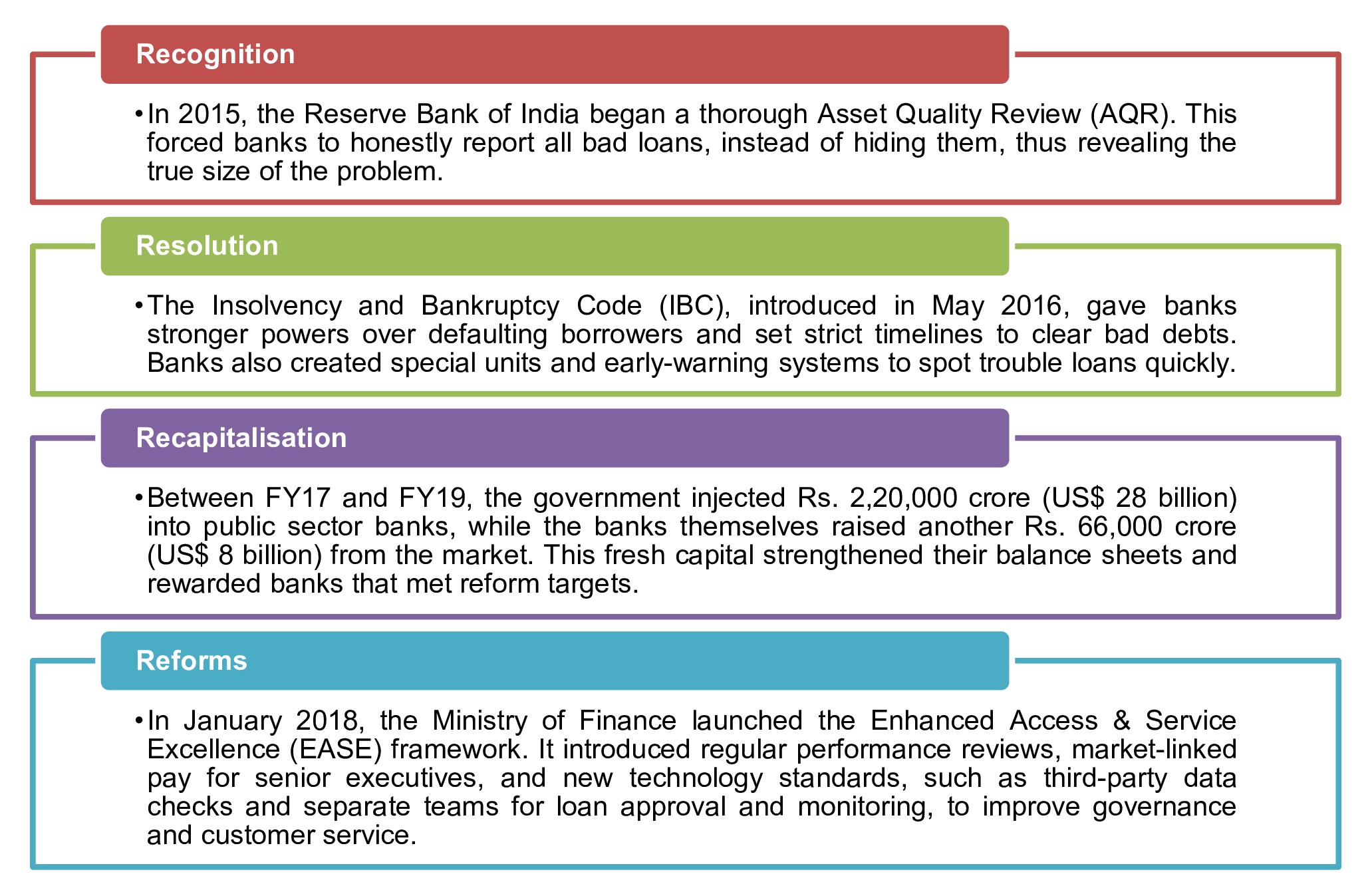

The government’s response to the banking crisis was encapsulated in the comprehensive 4Rs strategy: Recognition, Resolution, Recapitalisation, and Reforms. This framework represented a marked departure from previous ad-hoc approaches to banking problems and demonstrated a clear understanding that sustainable recovery required addressing both the symptoms and underlying causes of the crisis.

The government’s 4Rs strategy tackled the banking crisis in four clear steps.

Conclusion and strategic recommendations

The transformation of India’s Public Sector Banks from crisis-ridden institutions to profitable and efficient financial intermediaries represents one of the most successful banking sector reforms in recent global history. This turnaround demonstrates that with appropriate policy frameworks, adequate resources and sustained commitment, even deeply troubled financial institutions can be restored to health and profitability. The journey offers valuable lessons for other countries grappling with similar challenges in their banking sectors.

The success of the PSB transformation can be attributed to several key factors. First, the comprehensive nature of the 4Rs strategy ensured that reforms addressed both symptoms and the underlying causes of the crisis. Second, the political commitment to the reform process, demonstrated through substantial financial support and institutional changes, provided the necessary foundation for transformation. Third, the professional management of the reform process, with clear timelines and performance indicators, ensured accountability and momentum.

Moving further, India’s PSBs are in a good position to meet the country’s economic growth needs and uphold their social obligation of financial inclusion and development. They have boosted their balance sheets, created better governance structures and obtained more technological capabilities that offer a robust base of growth. Nonetheless, they must remain innovative and dynamic to keep up with a fast-changing financial environment.